Inflation vs Deflation vs Stagflation: Why Your Money Buys Less Coffee (And Why That's Actually Sometimes Better Than the Alternative)

By: Compiled from various sources | Published on Feb 01,2026

Category Intermediate

Description: Understand inflation, deflation, and stagflation—what they mean, how they affect your money, and why central banks obsess over these economic conditions. Economics explained without the jargon.

Let me tell you about the moment I realized inflation wasn't just an abstract economic concept but something actively stealing my purchasing power while I watched helplessly.

I'd been buying the same morning coffee for three years—medium latte, nothing fancy. In 2020, it cost $3.50. By 2022, it was $4.25. By 2023, $5.00. Same coffee, same size, same shop. But my money was buying 30% less coffee than three years earlier.

My salary had increased maybe 8% total over those three years. My coffee expenses had increased 43%. The math was depressing. I was working the same hours, earning nominally more money, but could afford less coffee—and coffee was just the visible example. Rent, groceries, gas, everything had quietly gotten more expensive while my paycheck crawled upward.

That's inflation. Not the definition you'd read in an economics textbook—it's the slow, persistent erosion of your money's purchasing power that makes you feel like you're running on a treadmill that keeps speeding up.

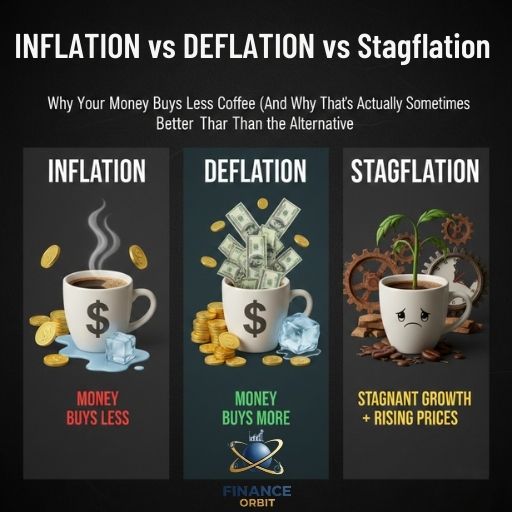

Inflation vs deflation vs stagflation explained matters because these aren't abstract academic concepts—they're the economic conditions that determine whether your savings grow or shrink in real terms, whether you can afford a house, whether your salary raise actually improves your life or just keeps you even.

What is inflation and deflation in practical terms means understanding that prices generally go in one direction (up—inflation) but can occasionally go the other direction (down—deflation), and each scenario creates different problems for your financial life and the broader economy.

Economic inflation effects aren't universally bad, and deflation isn't universally good, which confuses people. A little inflation is actually healthy. A lot of inflation destroys savings and destabilizes economies. Deflation sounds good (stuff gets cheaper!) but creates devastating economic spirals. And stagflation is the nightmare scenario—everything wrong at once.

So let me walk through inflation, deflation, and stagflation differences with real examples of how they've played out historically, what causes each condition, how they affect your actual money and daily life, and why central banks desperately try to maintain 2% inflation rather than 0% or 5% or deflation.

Because that $5 latte isn't just expensive coffee. It's monetary policy explained in caffeine.

What Inflation Actually Is (Beyond "Prices Go Up")

Inflation is the rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising, consequently eroding purchasing power. More simply: your money buys less over time.

The technical definition: Inflation is measured as the percentage change in a price index (usually the Consumer Price Index—CPI) over a period. If CPI increases 3% year-over-year, that's 3% inflation. This means a basket of goods that cost $100 last year now costs $103.

What this means practically: If you have $10,000 in cash and inflation is 3% annually, that money loses 3% of its purchasing power each year. After one year, your $10,000 buys what $9,700 would have bought previously. After ten years at 3% inflation, your $10,000 has the purchasing power of about $7,400. The number in your bank account stays the same, but its real value declines.

Why inflation happens—the causes:

Demand-pull inflation occurs when demand for goods and services exceeds supply. Too much money chasing too few goods. Example: Pandemic stimulus checks put more money in people's hands, they wanted to spend it, but supply chains were disrupted and couldn't produce enough goods to meet demand. Prices increased until demand and supply rebalanced.

Cost-push inflation occurs when production costs increase, forcing producers to raise prices. Example: Oil prices spike, increasing transportation costs for all goods, companies pass these costs to consumers through higher prices.

Built-in inflation (or wage-price spiral) occurs when workers demand higher wages to keep up with rising costs of living, companies raise prices to cover higher wages, which causes workers to demand even higher wages. This is the self-reinforcing cycle central banks fear.

Monetary inflation occurs when too much money is printed relative to economic output. More dollars competing for the same amount of goods means each dollar is worth less. This is the "printing money causes inflation" mechanism, though the relationship is more complex than simple money supply.

The 2021-2023 inflation example combined multiple causes: Pandemic supply chain disruptions (reduced supply), stimulus payments and savings accumulated during lockdowns (increased demand), Russia-Ukraine war disrupting energy and food supplies (cost-push from commodities), and extremely low interest rates encouraging borrowing and spending (monetary factors). Multiple causes created the highest inflation in 40 years—peaking around 9% in mid-2022.

Types of inflation by severity:

Creeping inflation is 1-3% annually—generally considered healthy and normal. Prices rise slowly and predictably.

Walking inflation is 3-10% annually—concerning but manageable. Starts eroding purchasing power noticeably.

Galloping inflation is 10-50% annually—serious economic problem. Savings evaporate, economic planning becomes difficult.

Hyperinflation is 50%+ monthly (not annually—monthly). Catastrophic. Currency becomes worthless. Classic examples: Weimar Germany (1920s), Zimbabwe (2000s), Venezuela (2010s-2020s). Wheelbarrows of cash to buy bread. Complete economic collapse.

Winners in inflation: Borrowers (debt becomes cheaper in real terms—if you borrowed $100,000 and inflation is 5%, you're effectively paying back with money worth 5% less each year). Asset owners (real estate, stocks, commodities often appreciate with or faster than inflation). People with salaries indexed to inflation.

Losers in inflation: Savers (cash loses purchasing power). Fixed-income retirees (pension payments don't increase with inflation). Lenders (repaid in less-valuable currency). People on fixed salaries that don't keep up with inflation.

Moderate inflation (2-3%) is generally considered optimal—enough to discourage cash hoarding and encourage investment and spending, but not enough to destroy purchasing power rapidly.

What Deflation Actually Is (And Why It's Terrifying)

Deflation is the opposite of inflation—the general level of prices is falling, meaning your money increases in purchasing power over time. This sounds great until you understand the economic consequences.

The technical definition: Deflation is measured as negative inflation—the price index (CPI) decreases year-over-year. If CPI falls 2%, that's 2% deflation.

What this means practically: If you have $10,000 and deflation is 2% annually, that money gains 2% purchasing power each year without you doing anything. After one year, your $10,000 buys what $10,200 would have bought previously. Sounds fantastic, right?

Why deflation is actually terrible—the deflationary spiral:

Consumers delay purchases because they expect prices to fall further. Why buy a car today for $30,000 if it'll cost $29,000 next month and $28,000 the month after? This rational individual behavior becomes economic disaster collectively.

Businesses see falling demand as consumers delay purchases. Lower demand means lower revenue. Companies respond by cutting production, laying off workers, and reducing investment.

Unemployment increases as businesses cut costs. Unemployed people have less money to spend, further reducing demand.

Wages fall as labor market weakens. Workers have less bargaining power, accept lower wages or get laid off.

Debt burden increases in real terms. If you borrowed $100,000 and deflation is 3%, you're effectively paying back with money that's 3% more valuable each year. The number you owe stays the same, but its real burden increases. This is devastating for borrowers—mortgage payments, student loans, business debts all become harder to service.

Businesses and consumers default on debts they can't afford, causing bank failures and credit freezes.

Investment collapses because why invest in a business or project if you can just hold cash and watch it gain value? Cash becomes the best performing "asset," so money flows out of productive investment into hoarding.

The economy contracts as all of these factors feed on each other. Falling prices → delayed spending → lower business revenue → layoffs → less spending → further price falls. This self-reinforcing downward spiral is extremely difficult to escape.

Historical examples:

The Great Depression (1930s) featured severe deflation in the U.S.—prices fell about 10% annually from 1930-1933. Unemployment reached 25%. Banks failed. Economic output collapsed. The deflationary spiral took a decade and a world war to finally reverse.

Japan's Lost Decades (1990s-2010s) experienced periodic deflation and near-zero inflation for over 20 years. The economy stagnated despite massive government stimulus efforts. Growth was minimal. This is the modern cautionary tale that terrifies central banks—once deflation takes hold, escaping is incredibly difficult.

Why deflation is so hard to fix: During inflation, central banks can raise interest rates to cool demand. This is painful but works. During deflation, they can cut interest rates to stimulate spending, but once rates hit zero (the "zero lower bound"), traditional monetary policy stops working. You can't have significantly negative interest rates—people would just hold cash rather than deposit it in banks charging them to hold their money.

Winners in deflation: Cash holders (money gains purchasing power). Lenders (repaid in more-valuable currency). People on fixed incomes if their income doesn't fall with deflation.

Losers in deflation: Borrowers (debt burden increases in real terms). Asset owners (real estate, stocks typically fall in value). Business owners (revenue falls, debt burden increases). Workers (unemployment rises, wages fall).

The counterintuitive reality: Central banks actively try to prevent deflation even though falling prices sound consumer-friendly. They'd rather have 2% inflation than 0% or -2% deflation because the economic consequences of deflation are so catastrophic.

This is why you occasionally hear economists and central bankers say things like "inflation is concerning but manageable; deflation would be a disaster." They're not being hyperbolic—the deflationary spiral genuinely is worse than moderate inflation.

What Stagflation Is (The Nightmare Scenario)

Stagflation combines the worst of both worlds: stagnant economic growth (or recession) plus high inflation. The economy isn't growing, unemployment is rising, yet prices are increasing rapidly. This shouldn't happen according to traditional economic theory, but it does.

The technical definition: Stagflation is high inflation combined with high unemployment and stagnant demand in the economy. Specifically, rising prices while GDP growth is low or negative and unemployment is elevated.

Why this is terrible: Normally inflation occurs during economic growth—demand is high, unemployment is low, wages are rising, and the economy is overheating. Or deflation/low inflation occurs during recessions—demand is low, unemployment is high, but at least prices aren't rising. Stagflation is the worst of both—your cost of living increases while jobs are scarce and the economy isn't growing. You're getting poorer in two ways simultaneously.

Why traditional solutions don't work:

To fight inflation, central banks typically raise interest rates to cool demand. This works when the economy is overheated. But if you raise rates during stagflation, you make the recession/stagnation worse—higher rates kill jobs and business activity.

To fight recession, central banks typically cut interest rates and increase spending to stimulate demand. This works when inflation isn't a problem. But if you cut rates and stimulate during stagflation, you make inflation worse—more money chasing the same limited goods.

The policy dilemma: Fighting one problem worsens the other. This is why stagflation is the nightmare scenario for policymakers—there's no good option, only choosing which problem to prioritize.

Historical example: The 1970s oil crisis is the classic stagflation period. OPEC oil embargoes caused oil prices to spike dramatically. This created cost-push inflation throughout the economy (everything became more expensive because energy costs increased). Simultaneously, the high energy costs slowed economic growth and increased unemployment. The U.S. experienced inflation reaching 13-14% while unemployment hit 9% and GDP growth was minimal or negative.

Fed Chair Paul Volcker finally broke stagflation in the early 1980s by raising interest rates to extreme levels—over 20% at peak. This caused a severe recession (unemployment reached 10.8%) but successfully crushed inflation. It was brutal medicine but ultimately worked.

Recent concerns: In 2022-2023, some economists worried about potential stagflation as inflation spiked while growth slowed. Central banks raised rates aggressively, accepting slower growth to fight inflation. So far (as of 2024), this hasn't developed into full stagflation—inflation has fallen while recession has been avoided, though growth has slowed. But the risk was real.

Causes of stagflation:

Supply shocks are the most common cause—something disrupts supply (oil embargo, pandemic supply chain breakdown, war affecting food/energy) causing cost-push inflation while simultaneously reducing economic output.

Poor monetary policy can also contribute—if central banks keep interest rates too low for too long while inflation is building, they can create stagflation when they're forced to raise rates rapidly later.

Structural economic problems like declining productivity, excessive regulation, or major technological disruption can cause stagnant growth while prices rise.

Winners in stagflation: Essentially nobody except owners of inflation-protected assets (commodities, precious metals, real estate in some cases, inflation-indexed bonds).

Losers in stagflation: Workers (unemployment high, wages don't keep up with inflation). Savers (cash loses value rapidly). Businesses (costs rise, demand weak). Borrowers if interest rates spike to fight inflation.

Stagflation is rare, but when it occurs, it's economically devastating and politically explosive. People are simultaneously losing jobs and watching their cost of living skyrocket—a combination that creates social instability.

How These Affect Your Personal Finances

Understanding these concepts abstractly is one thing. Understanding how they affect your actual money and financial decisions is what matters practically.

During inflation (what we're experiencing now-ish):

Your cash savings lose value. Money sitting in checking accounts earning 0% interest while inflation is 3-5% is losing purchasing power daily. A savings account earning 4.5% during 5% inflation is still losing 0.5% in real terms.

Your debt becomes cheaper in real terms. If you have a fixed-rate mortgage at 3% and inflation is 5%, you're effectively getting paid 2% annually to borrow (in real terms). This is why borrowing at low rates before inflation spiked was brilliant. Your mortgage payment stays the same nominally, but inflation erodes its real burden over time.

Your salary raise might not be a raise. If you got a 3% raise but inflation is 5%, you actually took a 2% pay cut in real terms. You're earning more dollars that buy less stuff. This is why people complain "I got a raise but feel poorer"—they're not wrong.

Asset prices often rise. Stocks, real estate, commodities tend to appreciate with or faster than inflation (though not always or evenly). This is why financial advisors tell you to invest rather than hold cash during inflationary periods.

What to do: Keep minimal cash (emergency fund only), invest the rest in assets that appreciate (stocks, real estate, I-bonds that are inflation-indexed), lock in low fixed-rate debt before rates rise further, negotiate salary increases that at least match inflation.

During deflation (rare but devastating):

Your cash gains value. Money in your mattress becomes more valuable without you doing anything. This incentivizes hoarding cash rather than spending or investing.

Your debt becomes more expensive in real terms. That mortgage or student loan becomes harder to pay as money becomes more valuable and wages potentially fall. The number you owe stays the same, but its real burden increases.

Your job is at risk. Deflation typically coincides with recession and high unemployment. Even if you keep your job, raises are unlikely and wage cuts are possible.

Asset prices fall. Real estate values decline, stock prices drop, everything becomes cheaper—which sounds good until you realize your house/portfolio is worth less and you might be unemployed.

What to do (if this ever happens): Pay off variable-rate debt aggressively, maintain emergency fund large enough to survive extended unemployment, avoid major purchases that could be cheaper later, be prepared for difficult job market. Honestly, individual strategies are limited during deflation—it's a systemic problem requiring government/central bank intervention.

During stagflation (the nightmare):

You're getting squeezed from both directions. Cost of living increasing while job market weakening. Prices rising while your income stagnates or falls. Debt might be getting cheaper in real terms, but if you lose your job you can't pay it regardless.

There's no safe harbor. Cash loses value to inflation. Assets are risky because the economy is stagnating. Jobs are scarce. Everything is difficult.

What to do: Focus on job security (make yourself indispensable, develop multiple income streams if possible), minimize unnecessary expenses, avoid new debt (interest rates are likely high), invest in inflation-resistant assets if you have money to invest (commodities, inflation-protected bonds, real estate potentially), maintain larger emergency fund than normal. Mostly: batten down the hatches and survive until it passes.

Why Central Banks Target 2% Inflation

You've probably heard that the Federal Reserve, ECB, Bank of England, and other central banks target approximately 2% inflation. Why 2% specifically? Why not 0% or 5%?

Why not 0% inflation?

Measurement error: Inflation is measured using price indices (CPI), which aren't perfect. They tend to overstate true inflation by 0.5-1% due to methodological limitations. If you target 0% measured inflation, you might actually be in mild deflation, which risks the deflationary spiral.

Downward nominal wage rigidity: This is economist-speak for "employers hate cutting nominal wages even when economically justified." If productivity falls or demand drops, employers need to reduce labor costs. With 2% inflation, they can keep wages flat (a real pay cut) without the demoralization of actual wage cuts. This provides economic flexibility.

Monetary policy effectiveness: With 2% inflation and corresponding nominal interest rates around 4-5%, central banks have room to cut rates to stimulate during recession. If inflation is 0% and rates are 2%, they have less room to cut before hitting zero. The 2% inflation target provides buffer space for monetary policy.

Encourages spending and investment: With 2% inflation, holding cash loses value gradually, encouraging people to spend or invest. This keeps money circulating through the economy rather than hoarded.

Why not 5%+ inflation?

Erodes savings and purchasing power too quickly. Moderate inflation is manageable; high inflation destabilizes.

Creates uncertainty that makes long-term planning difficult for businesses and individuals.

Risks accelerating into galloping inflation or hyperinflation if not controlled.

Hurts fixed-income people (retirees especially) whose income doesn't keep pace.

The 2% target is a compromise: High enough to avoid deflation risk and provide monetary policy flexibility, low enough to preserve purchasing power reasonably well and maintain economic stability. It's not magic—some economists argue for 3-4% targets—but it's become the consensus among major central banks.

How they achieve it: Primarily through interest rate policy (raising rates to cool inflation, cutting rates to prevent deflation) and sometimes through quantitative easing (buying bonds to inject money) or tightening (selling bonds to remove money). The repo rate discussions from earlier articles—that's the mechanism for implementing this policy.

Real-World Examples: Inflation Through History

Understanding historical episodes helps contextualize current situations.

Weimar Germany hyperinflation (1921-1923): Inflation reached absurd levels—prices doubled every few days at peak. A loaf of bread cost billions of marks. People were paid twice daily and spent money immediately because it would be worthless by evening. Caused by printing money to pay war reparations and government debts. Destroyed the middle class, destabilized society, and contributed to conditions enabling Hitler's rise.

U.S. 1970s stagflation: Already discussed—combination of oil shocks, loose monetary policy, and structural economic issues created high inflation (13-14% peak) with high unemployment (9%) and stagnant growth. Took brutal interest rate hikes (20%+ rates) and severe recession to break.

Japan's deflation (1990s-2010s): Asset bubble burst in early 1990s, triggering deflation and economic stagnation that lasted decades. Despite zero interest rates and massive government stimulus, Japan couldn't escape the deflationary trap for 20+ years. This is the modern cautionary tale.

Zimbabwe hyperinflation (2000s): Government printed money to pay debts and fund operations. Inflation reached 89.7 sextillion percent year-over-year in November 2008 (not a typo—sextillion). Currency became worthless. $100 trillion Zimbabwe dollar notes were printed. Economy collapsed. Eventually abandoned their currency entirely and adopted U.S. dollars and other foreign currencies.

Post-COVID inflation (2021-2023): Combination of supply chain disruptions, stimulus spending, pent-up demand, and energy price spikes created highest inflation in 40 years in many developed countries. Peaked around 9% in U.S., higher in Europe. Central banks responded with rapid interest rate increases. As of 2024, inflation has fallen significantly but remains above 2% target in many places.

These examples show inflation/deflation aren't abstract—they have real, often devastating consequences for societies and individuals.

The Bottom Line

Inflation is rising prices eroding purchasing power. Moderate inflation (2-3%) is healthy and normal. High inflation (5%+) is problematic, destroying savings and creating instability. Causes include demand exceeding supply, rising production costs, or excessive money printing.

Deflation is falling prices increasing purchasing power of money. Sounds good but creates devastating economic spirals—consumers delay purchases, businesses cut production, unemployment rises, debt burdens increase, economy contracts. Extremely difficult to escape once started.

Stagflation combines stagnant economy with high inflation—the worst of both worlds. High unemployment AND high inflation simultaneously. Traditional policy tools don't work well because fighting one problem worsens the other.

For your personal finances: During inflation, minimize cash holdings, invest in appreciating assets, lock in fixed-rate debt, negotiate raises matching inflation. During deflation (rare), focus on job security, pay down debt, maintain large emergency fund. During stagflation, diversify income, minimize expenses, avoid new debt, maintain flexibility.

Why central banks target 2% inflation: Balance between avoiding deflation risk and preserving purchasing power, provides monetary policy flexibility, encourages spending and investment without destabilizing economy.

The current situation (2024): Most developed countries are in moderate inflation (3-4%) following the 2021-2023 spike. Central banks raised rates aggressively. Inflation is falling toward target levels but isn't there yet. The economy has slowed but avoided recession so far in most places. We're in that delicate phase where central banks are trying to achieve a "soft landing"—reducing inflation without triggering recession.

Understanding these concepts helps you make better financial decisions, understand why your money feels like it buys less despite earning more, and contextualize economic news and policy decisions.

That $5 latte isn't just expensive coffee. It's monetary policy, supply and demand, and economic forces playing out in your daily life.

Now you know why it costs what it does.

And why central bankers lose sleep trying to keep it from becoming a $50 latte (hyperinflation) or a $0.50 latte that nobody buys because they're waiting for it to hit $0.25 next week (deflation).

Economics is just life with numbers attached.

And your coffee budget proves it.

You're welcome.

Now go check if your savings account interest rate is actually keeping up with inflation.

(It's probably not. Time to invest that money somewhere productive.)

Comments

No comment yet. Be the first to comment